Interviewer: “So why do you want to work at the Bureau of Surrealist Research?”

Interviewee: “I’ve always dreamed about working here.”

The existence of the Bureau of Surrealist Research was just one of the interesting tidbits we learned about at the The Colour of My Dreams: The Surrealist Revolution in Art at the Vancouver Art Gallery May 28, 2011 – October 2, 2011. (On the drive up from Seattle we came with the interviewer/interviewee joke.) The brochure features Claude Cahun (1894 – 1954) in Self portrait (as weight trainer) (1927). The other iconic imagery used as part of the promotion for the exhibition includes Edith Rimmington (1902 – 1986) The Oneiroscopist (1947) and Joan Miró (1893 - 1983) Ceci est la couleur de mes rêves (1925). Oneiroscopist means a specialist in looking at dreams – appropriate for the surrealists - and Miró’s piece, with the translated title this is the color of my dreams, is the source of exhibition title.

Edith Rimmington – Oneiroscopist (1947) and Joan Miro (1925) Ceci est la couleur de mes rêves

So what is surrealism? Surrealism is a cultural movement (not an art movement or style) that began in the early 1920s and that the Manifesto of Surrealism (1924) describes as “[p]ure psychic automatism by which it is intended to express, either verbally or in writing, the true function of thought. Thought dictated in the absence of all control exerted by reason, and outside all aesthetic or moral preoccupations.” And, that “[s]urrealism is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of association heretofore neglected, in the omnipotence of the dream, and in the disinterested play of thought. It leads to the permanent destruction of all other psychic mechanisms and to its substitution for them in the solution of the principal problems of life.” Automatism is spontaneous creation such as a drawing or writing with no conscious censorship. People, other movements, and events that came before surrealism like Freud, Dadaism, and World War I guided how the surrealist movement developed. It was a time of change and the surrealist motto was “Transform the World – Change Life”.

It is interesting to note that initially painting, as a surrealist activity, was emphasized very little in the manifesto; yet, it is painting that comes to mind most readily when talking about surrealism, especially the works of Dalí. Some early surrealists thought that the trouble with painting was that the expression (i.e. the mechanics) would get in the way of the automatic response so sought after as pure surrealism. The idea of letting automatism take hold and guide your creations is an intriguing one for those (like us) so used to executing a certain degree of control over our output – for work or pleasure.

A theme explored in the exhibition is the connection between First Nations art of the Pacific Northwest Coast and Alaska and surrealism. The surrealist artists Kurt Seligmann and Wolfgang Paalen visited the Northwest in in the late 1930s. Others like Andre Breton and Max Ernst purchased Northwest art. The surrealists were by accounts moved by the indigenous ceremonial art, drawn to the authentic nature of the work. However, as the essay Scavengers of Paradise by Colin Browne that appears in the exhibition guide points out: “…the surrealist relationship with the ceremonial objects of North America was complex, fluid and often naively idealistic. Many surrealist artists became collectors of primitive art but were unaware of the provenance or function of the objects they acquired …”.

The exhibit was broken into themed sections: Revolution by Night; The Colour of My Dreams; Behind the Screen; Spaces of the Unconscious; The Surrealist Object; Myths, Maps, Magic; The Lure of the Pacific Northwest; and Anatomies of Desire. On display there are several types of media: publications, photos, paintings, collage, sculpture, film, and objects. But, we confess it was really the paintings that grabbed us the most as can be deduced for the list of what we found interesting. Though, we do have a newfound appreciation of Man Ray (1890 - 1976); a number of his photographs and rayographs (really photograms) are included in the exhibition.

What we found interesting at the exhibition:

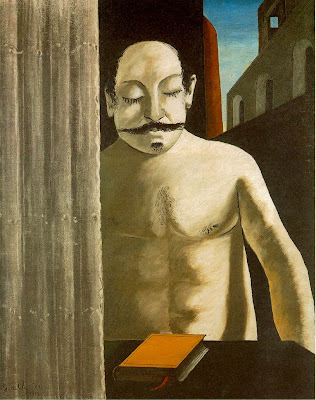

- Georgio di Chirico (1888 – 1978) was an important figure to the surrealists, a “haunting father”. The exhibit starts with de Chirico’s La cerveau de l’enfant or The Child’s Brain (1914). As a side note, it is interesting (for us) to see our reaction to di Chirico’s work in an exhibition in Palermo, La Metafisica continua. We did not like it.

Georgio di Chirico (1914) La cerveau de l’enfant or The Child’s Brain

- Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1873) seemed to flirt on the edges of surrealism.

- Kurt Seligmann (1900 – 1962): Seligmann’s The Four Temperaments (1946) or The Meeting of the Elements (1939) could have been easily at home on a Yes album cover. Roger Dean is the artist behind the Yes album covers. We wonder if he was influenced by Seligmann’s biomorphic forms.

- Joan Miró (1893 - 1983) Miró’s work Photo: ceci est la couleur de mes rêves. (1925) lends its name to the exhibition title. Such a simple and elegantly conceived work.

- Claude Cahun (1894 – 1954) was a woman. Not until after the exhibit did we realize he was a she.

- André Masson (1896 - 1987): Masson’s Meditation on an Oak Leaf (1942) is a crazy, contorted study. The information card describing the work said that Masson called it a “triumphant tellurism” style. Tellurism has to do with the hypothesis of animal magnetism put forth by Dr. Keiser. Masson’s The Metaphysical Wall (1940) was in the last room of the show and is a beautiful work.

- Wilhelm Freddie (1909 - 1995). Part of the Dutch surrealist movement, Freddie’s The Prayer (1940) is a stark, simple painting with a deflated figure praying at the very bottom of a dark purple canvas.

- Leonora Carrington (1917 – 2011). Carrington’s The House Opposite (1945) is a dreamlike scene not so different than the number of Renaissance domestic scenes we saw in Florence, just a little more surreal.

Leonora Carrington (1945) The House Opposite (detail left and right)

- Yves Tanguy (1900 – 1955). His work seems to have its own symbolic language, fragments of the symbols scattered here and there about eerie landscapes such as in The Doubter (1937) and Death Watching His Family (1927) – both in the exhibition.

- Exquisite corpse. Le cadavre – esquis – boira – le vin – nouveau or “the exquisite corpse will the drink the new wine.” is a method the surrealist used to create collaborative work. The works in this part of the exhibit were fascinating. Related methods included dessign collectif or collective drawing. An interesting example is the work Le jeu de’oie (1929) – The Game of Goose. The circular board game was created by André Breton, Suzanne Muzard, Jeannette Tanguy, Pierre Unik, Georges Saboul, and Yves Tanguy.

- Joseph Cornell (1903 – 1972) and his “poetic theatres” like The Crystal Cage (Portrait of Bernice) (1943 – 1960s). A fictional heroine Bernice, a young girl who performs ingenious scientific experiments inspired by the sights and sounds of the world.

- Hans Bellmer (1902 – 1975) and his arranged, life-sized, pubescent poupées (dolls) evoked a bit of wincing on our part and that fact alone made us wonder about the punch of his work.

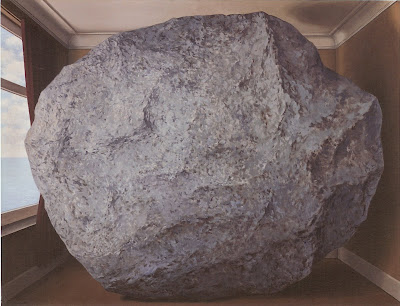

- René Magritte (1989 - 1967) – L’Anniversaire (1959) or the rock in the room, from a distance is wonderfully deceiving.

Magritte (1959) L’Anniversaire

The Colour of My Dreams: The Surrealist Revolution in Art – Brochure

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments are moderated. If your comment doesn't appear right away, it was likely accepted. Check back in a day if you asked a question.