2019 Previous Post - Introducing Scrapbook

2021 Followup Post - User Scenarios 2022 Followup Post - NL Query Engine

References

Our Digital Scrapbook

Scrapbook is a project we’ve been working on for several years. In technical terms, it’s a cross between a Personal Information Management (PIM) system and a Personal Knowledge Base (PKB). In plain English, it’s a collection of everything we think is important in our lives stored and accessed digitally. We’ve described Scrapbook in detail in the 2017 blog post

A Personal Information Management System: Introducing Scrapbook. In 2018, we created a free simplified version called

Scrapbook101 on GitHub for those with a programming background and interest in trying it out.

The purpose of this post is to expand on ideas introduced previously. Specifically, we will talk about what we’ve learned and where we have gaps, as well as talk about some of our inspirations for creating Scrapbook. In the process of writing this piece we encountered interesting references which are introduced and explained throughout this piece as well as summarized in the

References section. We have discovered many proposals and some actual systems (and services) that address the personal data management space in one way or another. The efforts span corporate and government research as well online service offerings and communities.

If you want to skip the background (

Compass Points) and thoughts on sharing data (

Digital Presence), and see some examples of Scrapbook in action, go to the

Scrapbook Themes section. There you will find images and animated GIFs that will give you a good idea of Scrapbook’s capabilities.

(

toc)

Compass Points

There are four key influences behind Scrapbook.

- The 1945 work of Vannevar Bush who introduced us to memex, a device designed to be an intimate supplement to human memory.

- The 2002 Microsoft Research project MyLifeBits, which expanded on the 1945 ideas of Vannevar Bush.

- The idea of a cabinet of curiosities or a collection of objects that are important or instructive to their collector.

- The 1995 science fiction novel The Diamond Age: Or, A Young Lady's Illustrated Primer by Neal Stephenson, in which Stephenson uses the idea of primer or vademecum that teaches its owner about the world.

Memex

In the 1945 Atlantic article

As We May Think, the American engineer, inventor and scientist

Vannevar Bush (1890 – 1974) introduced the term memex. (He used lowercase in the article and we will do so as well.) Bush coined the term to refer to a machine “in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory.” Bush’s memex was a desk with screens, a keyboard, and some controls all sitting on top of a microfilm repository.

Why did Bush conceive of the memex? It seems he was worried about the “growing mountain” of research data scientists had to be a master of while simultaneously dealing with increasing specialization in their fields. Bush goes on to make the point that the world had arrived at the point of “cheap complex devices” to help with mastering the mountain of information, namely the memex.

In the article, Bush makes the point that the human mind works by association and therefore, stored material in memex should facilitate users thinking and working with the material associatively. Bush envisioned users following “associative trails” that tied information together to facilitate browsing through data just like the human mind does with thoughts and ideas.

While Bush was thinking about information explosion in the context of a working scientist, we believe that information explosion is equally applicable to the average person managing their own life data and stories. A memex for a person’s personal data would be very useful. We are surprised that 75 years later Bush’s idea hasn’t really taken off and the average person doesn’t already have their own memex. We hear constantly from friends and family about the overwhelming nature of media – be it organizing photos, keeping track of ideas, tracking recommended books and films, or remembering things. Yet, the products or services to help don’t exist or are locked in a service or framework that is inflexible and makes your personal data a commodity.

Some key quotes from Bush’s article with our commentary:

- “Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanized private file and library. It needs a name, and, to coin one at random, ‘memex’ will do. A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory.”

- “Most of the memex contents are purchased on microfilm ready for insertion. Books of all sorts, pictures, current periodicals, newspapers, are thus obtained and dropped into place.”

- The Scrapbook user builds his own body of content that may include pieces of other data and information dropped in place, but overall the Scrapbook process requires more user involvement. Experience and stories can’t be purchased and dropped in place.

- “Presumably man's spirit should be elevated if he can better review his shady past and analyze more completely and objectively his present problems. He has built a civilization so complex that he needs to mechanize his records more fully if he is to push his experiment to its logical conclusion and not merely become bogged down part way there by overtaxing his limited memory. His excursions may be more enjoyable if he can reacquire the privilege of forgetting the manifold things he does not need to have immediately at hand, with some assurance that he can find them again if they prove important.”

- The phrasing Bush used in the above excerpt “bogged down” aligns with principle #1 of Scrapbook dealing with archival data and not getting bogged down – and at times paralyzed – by how to save and find data that might be useful in the future.

Throughout his life, Bush periodically updated his proposed memex with the latest technology: microfilm was to be replaced with magnetic tape which was to be replaced by crystals. However, by the time of Bush’s death in 1974, no memex machine was ever built.

(

toc)

MyLifeBits

We started Scrapbook about the same time we became aware of the 2002 Microsoft Research paper

MyLifeBits: fulfilling the Memex vision. At the time, the vision put forth in the MyLifeBits project seemed daunting and far off in the future. Upon reading the article again in 2019, the ideas seem less daunting because in the ensuing years we all have experienced many of the ideas put forth in the paper.

MyLifeBits is a digital personal lifetime storage framework/system, a database of resources (media such as video, audio, photos, documents) and links built around four principles:

- No strict hierarchy is enforced with resources. Collections and search are used instead for organization.

- Many visualizations should be supported to view resources and links.

- Annotations are critical to non-text media.

- Authoring should be via transclusion, two-way links, that is referencing and actual including text from related resources to make up a compound document.

MyLifeBits builds on the premise that you should be able to save all your resources (media), make annotations about them, and create links between them thereby creating a usable personal storage system that fulfills the memex vision proposed by Vannevar Bush.

MyLifeBits annotations, linking, and interpretation should be somewhat familiar, albeit in a very modest way, to most users of a smart device. Many modern services and software take your media and present you with interesting ways to look at and enjoy. For example, have you received a video set to music with images of your last trip or week’s activities that was delivered to you, perhaps by Apple, Facebook, or Google without even asking for it? If so, the you have a glimmer of what MyLifeBits proposed. It’s slowly happening, just not necessarily with you in control.

While sharing some characteristics with MyLifeBits, Scrapbook was designed to be a type of personal information management system and less a storage system for all media. Scrapbook is organized around curated items that can then be associated with media resources, assigned a category, location, and other types of metadata. We believe that at its base, Scrapbook does share with MyLifeBits the idea that the user should be in control of telling their story. The MyLifeBits paper emphasizes that users should be enabled to tell stories with their media. MyLifeBits stories are “an extension of Bush’s [associative] trails”.

Excerpts and influential ideas from the MyLifeBits paper with our commentary:

“Supposing one did keep virtually everything – would there be any value to it? Well, there is an existence proof of value. The following exist in abundance: shoeboxes full of photos, photo albums & framed photos, home movies/videos, old bundles of letters, bookshelves and filing cabinets.” This was one of the problems we set out to address with Scrapbook: an alternative to accumulating physical media that provides a way to go back and find what we you want.

“Note that for all but video, the delete operation may well become obsolete: the user’s time for the delete operation will be more costly than the storage to keep the item. Keeping everything does not imply that the user will be overwhelmed by the size of their collection: it is easy to filter out objects by lack of use, lack of links, and/or a low rating annotation.”

“The pinnacle of value is achieved when the user constructs a ‘story’ out of media. By story, we mean a layout in time and space.” “Stories create the highest value for two reasons: first, because the user will select the best media to include in the story; second, because the user will attempt to present the media in the most compelling manner.” This is an area where Scrapbook currently falls short. We are working on ways to provide more story, or contextual narrative in two ways. The first is through software, i.e., AI, schemas that facilitate better narrative capture, improved UX, and ease of acquisition. The second way is through better annotation and editorial processes when creating or editing a Scrapbook item. When we create a description for a Scrapbook entry, we need to train ourselves to think of a reader, perhaps ourselves browsing 20 years from now when the present context is all but forgotten, or some other person with no prior context at all.

“Finally, we observe that your media may be most highly valued by your descendants. For your great-grandchildren to have any appreciation of your media at all, it is clear that annotations and stories are essential.” We think this idea of passing on a media collection that is well organized and annotated is not at all thought of these days even given the staggering number of photos taken daily or entries made in social media. Some solutions for what is loosely called digital death management are discussed below in the section Digital Presence.

“The UI should avoid making the user perform extra clicks (or, worse, open a new window). In particular, they should not have to click to find a dead end.” “We also want to minimize the action needed to have a sense of what something is…” This has been an area where we’ve also fallen short with our current Scrapbook UIs. There are dead ends in the UX (user experience) such that users not already familiar with “how it works” might not have a sense of what they are looking at, or how to follow a connection that might exist in the data. One way we are addressing this point is by implementing a hashtag system and rethinking navigation paradigms.

As of writing, we know of no implementations of MyLifeBits for general consumption.

From left to right: The Chamber of Art and Wonders at Ambras Castle - Innsbruck Austria, Fondazione Cariplo - Wunderkammer, Palazzo Falso Library - Malta, Wadsworth Athenaeum's Cabinet of Curiosities - Hartford Connecticut, USA.

From left to right: The Chamber of Art and Wonders at Ambras Castle - Innsbruck Austria, Fondazione Cariplo - Wunderkammer, Palazzo Falso Library - Malta, Wadsworth Athenaeum's Cabinet of Curiosities - Hartford Connecticut, USA.

(

toc)

Cabinet of Curiosities

In a general sense, a cabinet of curiosities is a collection of objects that have importance for their owner, who may or may not be the collector and curator of the objects. In a literal sense, a cabinet of curiosities can be a cabinet or container, but originally the term referred to a room housing such a collection. The idea of a cabinet of curiosities is generally identified with the Baroque period and 16

th century because it is during this time that pictorial records of such cabinets began to appear. However, the idea of a cabinet of curiosities goes back much further in history as humans have always collected in one way or another.

“The instinct to collect is universal but the instinct to curate is not.”

A cabinet of curiosities is often referred to by several German loan words, one of which is

Wunderkammer meaning “wonder room”. We like that idea that such a room (or space, cabinet, or container in any sense) is designed to cause wonder and curiosity. In fact, much of our wonder and curiosity for the subject came from seeing examples during visits to museums. In one visit to the Palazzo Vecchio of Florence back in 2007, we remember being awed by the

studiolo of Francesco I, a type of Wunderkammer.

Studiolos are small studios (you have the love the diminutive forms in Italian) where you could retreat to in your palace and pursue cultural interests.

Studiolos and Wunderkammers were sometimes one and the same or at least filled similar needs for their owners.

Studiolos, Wunderkammers and cabinets of curiosities in history were limited to those who could create and maintain them, often the wealthy, be they rulers, aristocrats or scientists. In other words, average people didn’t have a cabinet of curiosities. But today, anyone can create a cabinet of curiosities as demonstrated by Gordon Grice’s book

Cabinet of Curiosities: Collecting and Understanding the Wonders of the Natural World, an illustrated introduction to the wonders of natural history and the joys of being an amateur scientist and collector.

Objects in a

Wunderkammer are important to the owner in that they have stories behind them, stories that help the owner structure his universe of knowledge. One of the most celebrated examples is the cabinet of curiosities of Ole Worm (1588 – 1654), a Danish physician, natural historian and antiquary. His cabinet is described in his catalog

Museum Wormianum, published after his death. You can view the catalog here on

archive.org. An interesting recreation of Worm’s cabinet of curiosities has been permanently exhibited at the Natural History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen since 2011. The work by artist Rosamund Purcell is described with photos at

Atlas Obscura.

Three other Wunderkammer examples we would like to mention are at Ambras Castle in Innsbruck, the British Museum in London, and Palazzo Falson in Malta. We have visited all three and noted the theme of collection-as-understanding,

i.e., a collection as a curated world view.

- The Chamber of Art and Wonders at Ambras Castle in Innsbruck is described as an encyclopedic, universal collection that encompasses the entire body of knowledge known in the second half of the 15th century when its objects were collected and organized by Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria (1529 – 1595). Amazingly, the collection is still exhibited in its original location.

- The permanent exhibit Enlightenment: Discovering the World in the Eighteenth Century at the British Museum in London aims “to recreate the experience of a museum visitor in the early years of the British Museum (from its foundation in 1753 to the death of George III in 1820),” the tail end of the Age of Enlightenment which flourished between 1680 and 1820. And, while on the large side for a cabinet of curiosities, it certainly qualifies as one for the excitement, curiosity and wonder you get from wandering around inside it.

- The Palazzo Falson in the Mdina, Malta is a relatively new private residence turned into museum. It was the intimate and orderly library space that caught our attention. It is considered an unusually large collection. We lingered in that library for a while thinking about how it’s owner and collector Capt. Olof Frederick Gollcher OBE (1889-1962) must have felt sitting at the desk, beaming about how his ordered books reflected his world view.

Interesting you might be thinking, but what does this have to do with Scrapbook? Glad you asked and we hope you might have guessed the answer! For us Scrapbook is our cabinet of curiosities. Instead of the usual arrangement of antlers, coral, books, and creatures in jars, we have digital artifacts. Like a physical cabinet of curiosities, we still struggle with ordering data in Scrapbook in orderly and sensible ways. Instead of shelves and pigeonholes, we have data spread out over a flexible data taxonomy that is evolves as our understanding evolves. In our cabinet of curiosities Scrapbook, we are owner, collector, and curator. Like all cabinet of curiosities, Scrapbook enables us to recall and tell stories about the objects it contains.

Is it a stretch to say Scrapbook is a type of Wunderkammer? In a Wunderkammer, you can walk in and get close to objects. Maybe the objects can be picked up, touched, smelled, and otherwise examined. With Scrapbook, you can’t do that. Items are digital with just text and media to examine. And in that sense, Scrapbook will never replace a beautifully curated cabinet of curiosities and is not trying to do so. However, if you think about constructing a cabinet of curiosities with a collection of objects representing just your own personal known knowledge, you are talking about a lot of space. And, as we pointed out

in our 2017 introductory post on Scrapbook, one of the reasons why we developed Scrapbook was to reduce space taken by “objects” that had value in their content and meaning but not the physical space they took up. As the average person gets progressively more transient (

liquid times), maybe it’s time to start thinking about personal portable Wunderkammers that can make things easier for ourselves and the

planet.

From left to right: Byrthferth Enchiridion - Mysteries of the Universe; Epicteti Enchiridion - Angelo Politiano Latin translation (Basel 1554) page 1; Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook - a Vademecum for chemical engineers; The front cover of Neal Stephenson's The Diamond Age.

From left to right: Byrthferth Enchiridion - Mysteries of the Universe; Epicteti Enchiridion - Angelo Politiano Latin translation (Basel 1554) page 1; Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook - a Vademecum for chemical engineers; The front cover of Neal Stephenson's The Diamond Age.

(

toc)

An Illustrated Primer

When we read the 1995 science fiction novel

The Diamond Age: Or, A Young Lady's Illustrated Primer by Neal Stephenson, we were immediately struck by the idea of the primer in the story. The idea has floated around in our heads ever since. In the Diamond Age future, the primer is an advanced piece of nanotechnology that is part super-computer, part teacher and part friend for a young girl. The primer’s purpose is to:

- Educate and raise its owner to be capable of thinking for herself;

- React to its owner's environment and teach her what she needs to know to survive and develop;

- Steer its reader intellectually toward a more interesting life and grow up to be an effective member of society.

In the story, the primer and various copies of it fall into different hands and we see how each young girl turns out differently. The main character Nell’s interaction with the primer is at the heart of the story. Her primer’s front cover reads “YOUNG LADY’S ILLUSTRATED PRIMER a Propaedeutic Enchiridion in which is told the tale of Princess Nell and her various friends, kin, associates, &c..” Propaedeutic can be taken as “introductory” and enchiridion is another word for “handbook or manual”.

The primer’s inventor Hackworth describes how the primer bonds with its owner as a book that will “…see all events and persons in relation to that girl, using her as a datum from which to chart a psychological terrain, as it were. Maintenance of that terrain is one of the book’s primary process. Whenever the child uses the book, then, it will perform a sort of dynamic mapping from the database onto her particular terrain.” In other words, the primer adapts to new information and cues of the girl’s environment.

Scrapbook is so static compared to the primer! (Makes one think of the Elton John song “You’re So Static” from the 1974

Caribou album.) While Scrapbook can’t compete with science fiction, it does have one advantage: it is real and can be used. And, Scrapbook is adaptable even without nanotechnology. The adaptability comes from how we use Scrapbook, how we make corrections and additions and keep evolving the information and stories contained therein. We find that the more we use Scrapbook the more it becomes integrated into our lives. In this respect, building and using Scrapbook has become a part of our lives. It is our primer.

As pointed out in the article

Learning in the “The Diamond” (or, the digital) “Age”, while the primer is a technological wonder and is used as a solo activity, that doesn’t mean human relationships don’t matter. On the contrary, social interactions and human communication are fundamental. This is clearly demonstrated in the story by how the three girls with three different copies of the primer turn out differently based on the varying amounts of interaction and communication each had with her primer. The primers depend on a human “ractor” (remote interactive actor) who reads and interacts with the primer’s owner. In the case of the protagonist Nell, her primer interactions over many years were with the same “ractor” which lead to a strong relationship.

Vademecum is another curious word related to enchiridion that should also be mentioned while we are talking about the primer.

Vademecum also means roughly a “handbook or manual” that is always on hand. It derives from the Latin verb

vadere and literally translating as “go with me”. The primer is a type of

vademecum, something you would always want in your pocket or on hand for consultation. We think of Scrapbook in that way as well: something we always want on hand, which translates to availability on all devices.

(

toc)

Digital Presence

Striking a Balance

Above we discussed four key influences above which have guided our thinking behind Scrapbook over many years. In the course of writing this piece, we came across new and interesting ideas that we’ll mention in this section because we believe they raise pertinent questions related to ones we are trying to address with Scrapbook. One theme that we saw again and again is question of digital presence, that is, your online data and identity. The specific question is this: How much faith and data should you put in online services, yet avoid having your data used by these services in ways that you don’t know of, approve of or want?

On one hand, we have the idea put forward in the recent Washington Post piece,

What happened when I told Marie Kondo I have a better, higher-tech method of tidying up. In this piece, the author suggests that leveraging online services makes our lives easier. Instead of throwing digital assets away and tidying up

à la Marie Kondo and her motto “if it doesn’t spark joy, throw it away”, in the digital world we should be making better use of online storage services.

Keeping and not deleting is increasingly easier today. Our data is synchronized (usually automatically) to a cloud service and we don’t have to think about throwing anything away. This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be organized, just that throwing away digital assets due to limited space is increasingly less of a motivation these days. (In the 2002 MyLifeBits paper we discussed above, it was suggested that the delete operation might become.)

In addition, advances in artificial intelligence baked into online services make querying your data simple. For example, for photos there are timestamps, location information, face recognition and auto-tagging that now come with most services. Is it not is a wonderous thing that on you phone you can open your photo album and type “cheese” to return all photos having something to do with cheese without having done anything special to make that happen?

Wondrous or something to be worried about? What do these services know about us for having that ability? How are they commoditizing us or our data?

For an alternative perspective on the question of embracing online services, namely not using them at all, see the interesting Gizmodo article,

I Cut the 'Big Five' Tech Giants From My Life. It Was Hell, where the author endures life without the big five online services: Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, Google, and Amazon (FAMGA). Spoiler alert: the author doesn’t last long and goes back to using the services albeit using them more wisely.

So where does this leave us and our Scrapbook effort regarding online services? Before answering this, we need to clarify the consumption of services from the point of view of a consumer and that of an application. From the point of view of a consumer, we use all the usual consumer-focused services in one way or another. We buy on Amazon. We have photos auto-synchronized to Apple, Google, and Microsoft (OneDrive). We have Facebook, Snapchat and Instagram accounts. We try, to the best of our ability, to use these services in a targeted way. How so? We buy local when possible instead of resorting to Amazon for everything. We check into Facebook once every few weeks, rarely posting or building a timeline, partly as a trust issue and partly because it tires us to use Facebook. When we need these services, we log on and then log out after to minimize tracking. Furthermore, we have multiple email accounts and browsers for different tasks. And, we avoid logging into other services using our existing FAMGA accounts even if it’s sometimes more convenient than creating yet another account. As for saving photos in the cloud, we pay for (private) storage and we cross our fingers that our photos are not yet monetized.

For Scrapbook (software and data) the story is different because we are consuming online services as an application. Scrapbook runs and is hosted on paid-for Microsoft Azure services including storage, database, and application hosting. Doing so doesn’t entail any tracking of us or profiling of our data. Azure can’t read what we store because they don’t have the encryption keys for our data or see what we are querying for when using SSL.

Overall, we believe that you can’t and really don’t need to avoid using consumer-focused online services. You just need to use them wisely. Beware of bright new and shiny features that hook you into dumping more of your digital presence into a service in which you don’t understand how your data is being used or if you can even extract it in the future. You need to understand what any free services really cost regarding use of your personal data, identity, or habits – and when appropriate – opt instead to pay for those services to avoid sharecropping of your data.

(

toc)

Who’s in Control?

An idea similar to Scrapbook was proposed in 2007 by author Jon Udell in the post

Hosted Life Bits. At birth, each person would “in addition to a social security number, everyone gets a handle to a chunk of managed storage” that would follow them throughout life. The hosting would be a cross between public and private entities. How that would work remains to be seen in terms of access and control of that managed storage.

A similar effort was the DARPA

LifeLog project. Thankfully, the Pentagon

canceled the project in 2004, or at least claims to have. (You have to go to Wayback Machine

archive to see the original proposal.) From the initial proposal it was stated that “LifeLog will be able to find meaningful patterns in the timeline, to infer the user’s routines, habits, and relationships with other people, organizations, places, and objects, and to exploit these patterns to ease its task.” The objective of the LifeLog is to be able to trace the ‘threads’ of an individual's life in terms of events, states, and relationships. This made us immediately think of memex’s associative trails and MyLifeBits’ stories. The predictive nature – aka meaningful patterns – sounds wonderful, but that information and power it entails should rest in the hands of individuals not the government.

One group that is all about control is the

Indie Web community. You have to love the

Indie Web introduction on their why page “Whatever the reason, you’re done with sharecropping your content, your identity, and your self.” The use of the word

sharecropping is particularly impactful. We fully support the idea of not ceding important data about yourself to other interests that don’t benefit you.

Indie Web is about how to control your presence on the web and choosing the tools and services for doing so that don’t give away or sell your data or compromise your control. Scrapbook is

not focused on web presence and instead on personal information management and how it can be curated and used to tell/access your own story/history/narrative. Scrapbook doesn’t currently have any sharing or publishing functions. While these functions can of course be added, they have not been our goal thus far.

Alas, we are still not free from thinking about who controls our data even after death. We’re seeing in fact increasing discussion around

digital death management. Besides articles like this from lifehacker “

Five Things To Do When Planning For Your Digital Death”, there are services you can use to manage your after-death digital presence. For example,

If I Die will deliver notes to designated people after you die. Slightly more ambitious is the service

Digital Death with the catchy phrases like “you can’t take it with you” and “the society that lives online, will mourn online.” Whether you use a service or not, you need to be prepared for managing your digital presence long after you are gone.

What to do after we are gone is a problem we haven’t addressed or thought about. If anything, Scrapbook is currently more ephemeral than a service like Facebook. If we were to die or to lose interest, our hosting service would wipe our data, our services, everything within a year after our last subscription payment. There would be backups, but not something readily accessible. Maybe we should do a big print all command before dying? Perhaps physical media does have the last say.

Sound crazy?

Maybe not after seeing the Museum of History in Granite in Felicity Arizona discussed in our post

A Trip to Felicity. Felicity is in the southeastern corner of Imperial Valley County, a stone’s throw away from where the borders of California, Arizona, and Mexico meet. It is here that the French-American

Jacques-André Istel decided to record the history of humanity in granite. It’s sort of the ultimate stone Scrapbook, an outdoor Wunderkammer, the world according to Istel and his wife Felicia, namesake of the town, who did the research to present the stone summaries that effectively mix science, art, and humor. It’s almost certain that these granite panels will last well past Scrapbook or any current online service.

Views of the Museum of History in Granite in Felicity, California, USA.

Views of the Museum of History in Granite in Felicity, California, USA.

(

toc)

Scrapbook Themes

We have worked on Scrapbook since 2003. We kicked our work into high gear two years ago when we overhauled the guts of the system (

described in our 2017 introductory post) and started to seriously curate our data. In doing so we’ve learned a lot and had a couple of

a-ha moments along the way. What we describe below is an extension and update the

lessons learned we included in the 2017 post.

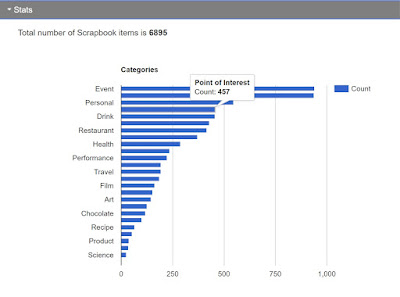

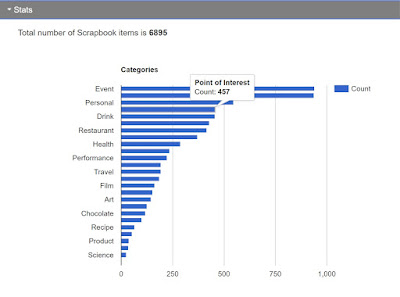

A Memory Extender

Offloading data from our minds into Scrapbook and not being stressed out about finding it again is a huge relief for us. We are freed from having to remember a myriad of facts and details, including the need to retain physical paperwork. In this capacity, Scrapbook has been a success. 6900 Scrapbook items with supporting assets of 40 GB help us retain the memorable, and sometimes the unmemorable details of our lives that we want to be able to recall if needed or desired. Examples include remembering the names of the children of an acquaintance, seeing what year we read a book and what we thought about it, figuring out the last time we had lunch with a friend, and many more non-critical but interesting queries. These 6900 items (so far) are organized across over 20 categories such as “Event”, “Point of Interest”, “Book”, “Film”, “Idea”, and “Correspondence”. 9 out of 10 times we can retrieve the details of something we “stored” in Scrapbook through a simple search query or natural language query. For the 1 out of 10 times that we don’t, the problem is usually that we had not curated the item(s) correctly or that our search queries are lacking.

The price we pay for not having a bunch physical files, boxes, etc. to store and sort through and instead the near instant recall of that all information is the time we’ve invested in the creation and maintenance of software and the time required for the entry and curation of content (aka Scrapbook items), with the latter taking the bulk of the time. (We define what curation means for us in the

Curation section below.)

If the content isn’t well-curated and entries are not sufficiently described, then Scrapbook is less memory “extender” and more memory “tickler”. Yet even while a minimally described/labeled entry might at best just tickle your memory, it is still nonetheless important.

Left: Category counts in Scrapbook. Center: Using the Travelmarx bot to query Scrapbook and show restaurants we ate at in Berlin with details of entry. Right: Using the Travelmarx bot to query Scrapbook for books read in 2014, listing them, and showing details for one.

Left: Category counts in Scrapbook. Center: Using the Travelmarx bot to query Scrapbook and show restaurants we ate at in Berlin with details of entry. Right: Using the Travelmarx bot to query Scrapbook for books read in 2014, listing them, and showing details for one.

(

toc)

Chasing Importance

Scrapbook is a Personal Information Management (PIM) system. Or, if you like the analogy, a digital bookshelf where we have organized items of different types. Items are stored and items are retrieved. And as we mentioned already, to this extent Scrapbook is successful. However, in our first blog post’s

Future Directions section, we also talked about making Scrapbook data more actionable. And at Travelmarx HQ, we often talk about extracting "value" or "meaning" from the data now and in some future environment either by us or some artificial intelligence agent.

But we've come to wonder if maybe we are overloading the capabilities of Scrapbook. For example, even if we had the tools in hand, what kind of meaning can be extracted from our PIM system? Do we even have the data in the right format? (Answer: probably not.)

Continuing along with this line of thought, we also realized that while Scrapbook currently stores data about things we care about, this data doesn’t always indicate what is important or relevant to us. As an analogy think of monitoring a person’s phone calls where you only know metadata of the calls: who, when, duration, and maybe location. With that information you could say something about that person's communication but not necessarily deeper questions like who the person's favorite friend was, the most important influence in that person’s life, or what was talked about. The metadata of the calls is useful but isn’t everything.

For another example, let’s go back to the bookshelf analogy. If you walked into a stranger’s house and examined their bookshelves full of books, knickknacks, and mementos you might form an idea of the person but what could you say about any of those items on the shelf and their importance in the life of that person?

The

a-ha moment we arrived at is that Scrapbook doesn’t

always capture what is important to us. As a specific personal example, let’s take the place where we spend a good chunk of any day hanging out with friends. This place is called Café Papavero. Could someone querying Scrapbook get an idea of the importance of Café Papavero in our daily lives? We put this question to the test and the results were mixed.

The experiment. Searching Scrapbook item titles and descriptions for " Café Papavero" we find about 20 items over the last 3 years. Searching just titles we see just 3 items. And we noted that we don't even have a Scrapbook entry for “Café Papavero” item itself because we take it for granted. Based on the number of found items and details included, someone might conclude Café Papavero is a place we’ve been a few times, and not much more than that. Nowhere in any of the search results do we describe how we feel about the café and how important it is to us.

In the example above and in other cases, we realize that without our specific knowledge or context included in the data, it’s hard to deduce meaning or importance from the search results. Furthermore, we realize that many common and important everyday things often don’t make it into Scrapbook.

Part of the problem is that being human, we take for granted things that are important to us and it doesn’t occur to us to record them. We are pretty good about capturing exceptional or outlier data (that could be important as well) but perhaps not as important to us long-term as something seemingly trivial and daily. Of course, this all can be addressed by rethinking about what gets entered and what gets said about entries. Taking a page out of the MyLifeBits project, there needs to be more “story” and less “data”.

We’ve wondered

if Scrapbook

were collecting the right information in the right format, could an avatar be created that draws from Scrapbook’s 6900 Scrapbook items and 40 GB of assets? Could such an avatar answer questions posed by someone say 10 or 100 years from now asking: “What kind of food do you like the most?”, “Are you the traveling type?”, “Which books influenced your thought the most?”

An effort called

Eternime is working on this exact problem. They want to preserve members’ digital legacy and create a digital avatar that would provide someone after your death the possibility of interacting with your memories, stories and ideas, almost as if they were talking to you. The service, started in 2014, is still in early access as of 2019. You can read more about it here in the New Yorker article,

How to Become Virtually Immortal.

Future avatars and self-flagellation for not always recording what’s important aside, we’ve tried to find a happy balance by aiming for a future that is within our lifetimes. That is, we want to have Scrapbook be relative to us currently and in our own futures. In 10 or 20 years, what questions might we ask and what do we need to do now data-wise now to satisfy our future selves.

(

toc)

But Can it Predict?

Ten years ago, we envisioned a Scrapbook with smart “agents” that would be always active and watching our Scrapbook data, ready to make corrections, offer suggestions, or even gamify the data if we wanted it, e.g., “Do you remember that time when…?” This is a vision of Scrapbook that is less one-way and more interactive, borrowing a bit from the

Diamond Age’s primer.

We envisioned that these agents would help us make better decisions about what we did and how we lived – in a very broad sense. None of that vision has yet been realized and here we are today with a corpus of 6900 entries that derives its meaning by what has been entered, the software features that tie it all together, and our interpretation of search results. Was that just wishful thinking or is it possible to do more with our data?

We were encouraged by the article “

Haystack: Per User Information Environment” (1999) that describes a digital information retrieval system. In the Haystack system, there are different types of data harvesters, two automated and one for human annotation. The authors point out that annotation by the user is the best source of information but also the least likely to happen. The automated data harvesters are probably the closest to what we envisioned 10 years ago.

Facebook has its agents, harvesters, AI algorithms or however you want to label them. For example,

Business Insider writes that Facebook algorithms have a pretty good idea of which post or picture is a memory that should be surfaced in their on-this-day feature. Apparently, being reminded of a good meal doesn’t make the cut. (Funny, a good meal for us does.)

As AI technology becomes more readily available to average coders and tinkerers like us, we can get ready for when we might have our own personalized and private data-harvesting agents. Getting ready means getting our data ready, including some of the following changes.

- Do more with ratings. We realized that we or some automated agent can’t make judgement or predictions if many Scrapbook items are not rated. Currently, rating is just applied to handful of categories where it is the most “obvious” such as books, films, museums, and restaurants. But we asked ourselves why not rate every item? That leads to the question of what does a rating mean for some categories like event, idea or people? Perhaps a better way to think about rating is as influence or relevancy. This is still an open question for us.

- Better curation/writing practices. This means including the backstory for each Scrapbook entry and explicitly stating its importance, for example, in the least by writing “this was important” or “this wasn’t that important”. At least, sentiment parsers (like the Facebook example above) of some future system we might implement would be able to glean what was important and what wasn’t.

- Investigate ways of representing relationships between Scrapbook items.

- Short term, we are implementing hashtags as connectors between Scrapbook items that would not otherwise be connected. There are several properties that already connect Scrapbook items together including category, location, date, and words used in titles and descriptions. Hashtags like #UNESCO, #HikingAroundBergamo, #BavariaTrip2016 and ##ZahaHadid can add additional tie together items to start to tell stories that span many items.

- Long term, we plan to model the connections between items in Scrapbook as a graph database. Currently, Scrapbook is focused on modeling and capturing the data on individual Scrapbook items (entities). As noted above, we try to surface relationships in various natural, if not ad hoc, ways such as assigning items to categories and using hashtags, as well as items being naturally related by date and location. However, we still are missing true relationships between items. This problem is a natural fit for graph database technologies which focus on both entities and relationships in a more natural way.

Left: Using the Travelmarx bot to query Scrapbook for #Dolomites and showing the details of one item. Center: Using Cortana to query Scrapbook for all postcards received, narrowing the search to just Florence, and showing details one. Right: Using the Scrapbook web interface, start with showing recent books, search for UNESCO sites using hashtag, drill in on day we went to Royal Greenwich Observatory to see what else we did that day.

Left: Using the Travelmarx bot to query Scrapbook for #Dolomites and showing the details of one item. Center: Using Cortana to query Scrapbook for all postcards received, narrowing the search to just Florence, and showing details one. Right: Using the Scrapbook web interface, start with showing recent books, search for UNESCO sites using hashtag, drill in on day we went to Royal Greenwich Observatory to see what else we did that day.

Curation – A Virtuous Cycle

Of the projects (memex, MyLifeBits, Haystack, and others) we reviewed, the curation process via writing descriptions or annotations is suggested as the best way to give context to user data but is also recognized as not always likely to happen. And while it may bog down some users, Facebook timeline is a good example of a curation process that works.

Scrapbook currently requires a great deal of user time inputting and curating data. We feel for us that the time spent is justified with the power and preciseness of the queries we can make. This is a tradeoff we are willing to make, but perhaps not others.

Going back to the cabinet of curiosities idea, with Scrapbook we are the collector and the curator. In the 16

th century when an item was added to a collection, the collecting (procurement of each object) was probably far harder and more expensive than the curation of the objects. In the digital age, it’s much easier to collect and more time consuming to curate. With each item we add, we find ourselves asking: “What does a digital object represent and how is it related to the rest of the objects in a digital collection?”

Therefore, we find ourselves in continual curation. And while our curation process is always improving,

i.e., getting quicker, we have a long way to go. On the software front, we are working toward a future where:

- Scrapbook is on all devices, always available, at our fingertips…a true vademecum. We find that using Scrapbook every day, and in time-critical situations helps us understand where it succeeds and where it fails. Currently, we can access Scrapbook on some devices (PC, tablet, phone) and with a few channels (web, bot, assistant). But we need to always look to more extensibility points. For example, we are exploring what it’s like to interact with Scrapbook only verbally and where that breaks down such that we need to see a screen or touch a keyboard.

- A more robust editorial system that supports:

- Entry of new items and editing of existing items as quickly and painlessly as possible. Our current process is a web form which isn’t optimal. It’s still too cumbersome for what should be quick single item updates or bulk editing. This is important because we’ve noted that to edit once and never touch a Scrapbook item again is not the norm. It typically takes several passes (create, save, edit, save, edit, save, and so on) to get an entry “correct”. Why? Sometimes the complete information for an item isn’t known during item creation and might not be available until days or months later.

- Flagging of items that need to be changed or edited. When we use Scrapbook every day, we notice corrections or updates to make, but don’t always have the time at that moment to fix them. A system to flag problems and save for later would go along way toward addressing data that is missing data, or that needs to be updated or corrected. Capturing those observations and channeling them into actual changes is currently onerous and needs to be streamlined.

Besides software improvements, we are also working on curation best practices such as:

- Be consistent in titles and writing descriptions. This seems straightforward as advice goes but it’s not always easy to follow.

- Take the time to enter a base level of context for an item or don’t enter the item at all because it will just create confusion later. We have found that adding garbage or incomplete entries is worse than not entering the entry at all.

- Avoid lumping distinct items into one entry to save time. We’ve noticed that when we do that, we end up spending more time trying to reconstruct what happened then if we had just spent the time entering the distinct items from the start. For example, let’s say we spend two days and one night in a city, visit two museums, and eat at two great restaurants. Ideally, we will create one travel entry, one hotel entry, two restaurant entries, and two museum entries. Furthermore, the entries should tell a little story or have anecdotes or observations from the trip.

- Revisit and revise data often. This is probably the most important curatorial practice. Going back and using the data leads naturally to correcting for sins of laziness, haste, and uncertainty when the item was initially created. Sometimes there’s worthwhile perspective we can add we simply didn’t have at the time. The more we use Scrapbook and the more it becomes important in our daily lives, the better the data gets as a natural outcome.

Left: Using the Skype connecting to Travelmarx bot to query Scrapbook for details on a point of interest we encountered in Kansas, a large Czech egg, and see what we wrote about it. Right: Using the Travelmarx bot to query for all items in Quito Ecuador, viewing an interactive map, finding an item of interest (Guayasamin Museum), and showing details of entry including encounter with an interesting person who gave us an informal tour.

Left: Using the Skype connecting to Travelmarx bot to query Scrapbook for details on a point of interest we encountered in Kansas, a large Czech egg, and see what we wrote about it. Right: Using the Travelmarx bot to query for all items in Quito Ecuador, viewing an interactive map, finding an item of interest (Guayasamin Museum), and showing details of entry including encounter with an interesting person who gave us an informal tour.

Data curation and creation are terms we use liberally in the post but haven’t defined precisely. What we mean by data curation is the management of data in three broad steps:

creation,

transformation, and

deletion. We define our data

creation phase as:

- Collect any assets (photos, videos, documents) to be associated with the new Scrapbook item.

- If the Scrapbook item represents a physical item, then we will have taken any necessary scans or photos. In this case, the creation of the new Scrapbook item is akin to an archive process.

- If the Scrapbook item doesn’t represent a physical item, there still may be assets like photos, video, or documents.

- Develop the textual content that will describe the Scrapbook item.

- Create the Scrapbook item.

- Enter a title and description based on the textual content.

- Assign attributes to the Scrapbook item such as category, date, geo location, path to assets.

- Associate assets to the new Scrapbook item.

After creation of a Scrapbook item, the

transformation phase begins, which can include:

- Edit textual information, specifically the title or description of the Scrapbook item.

- Change attributes of the Scrapbook item, category, date, geo location, modify date, etc.

- Add or remove assets associated with the Scrapbook item.

The transformation phase lasts until the item is deleted. (We currently don’t archive deletions.) The

deletion phase includes:

- Delete the item from Scrapbook.

- Remove any associated assets.

(

toc)

The Power of Location

In our first blog post on Scrapbook we wrote in the

Future Directions section that we would do more with geocoding and we have. Currently 45% (up from 0%) of our 6900 items have either a friendly location name (e.g., Seattle, WA or place address) that is geocoded to an extract latitude and longitude (i.e., 47.609722, -122.333056) or the geocode itself entered directly.

We have found that adding location to items allows us to do some interesting queries and visualizations. For example, we can ask questions such as the following:

- Show me postcards from France.

- Show me hikes in Washington State.

- Show me wines from Germany.

- Show me museums we’ve visited in Italy.

The output of these queries is a list and an interactive map. For geocoding and map production, we use Bing Maps. For more information, see

Geocode section in the Scrapbook101 documentation. (Scrapbook101 is a version of Scrapbook that doesn’t have all the bells and whistles we’ve built in but could be a good starting point for those wanting to build something themselves.)

The benefits we’ve seen as more of our development time has focused on the mapping features and consequently more of our everyday use of Scrapbook is mediated through maps include:

- We have more more fun using Scrapbook in the context of an interactive map. Looking at a map, and especially showing someone a map, of where we skied or hiked for example is much more informative and engaging than a mere list.

- We become more informed geographically. We are much more aware of where stuff comes from (e.g., wines, chocolates) and where we’ve been (e.g., restaurants, travel, points of interest) when we include precise location with Scrapbook items and plot them on a map. For example, see the images of wines (we drank) from Italy and France. From these maps, you can see wine drinking regions and start to ask questions about these areas and be more informed in future purchases or consumption.

- We spot more data inconsistencies and fix them when we view maps.

Left: Using the Travelmarx bot to query Scrapbook for hikes we did in 2014 and show interactive map. Center: Using the Travelmarx bot to query Scrapbook for hotels in England we stayed at, refine search to Yorkshire (North England) and view a map of the hotels. Right: Using the Travelmarx bot to query Scrapbook for any entries with location in Death Valley and show details of one.

Left: Using the Travelmarx bot to query Scrapbook for hikes we did in 2014 and show interactive map. Center: Using the Travelmarx bot to query Scrapbook for hotels in England we stayed at, refine search to Yorkshire (North England) and view a map of the hotels. Right: Using the Travelmarx bot to query Scrapbook for any entries with location in Death Valley and show details of one.

Left: An interactive map output from Scrapbook showing all wines we drank that came from France. Wines are clustered in regions like Bordeaux, Burgundy, and Provence. Right: An interactive map output from Scrapbook showing all wines we drank that came from Italy. Again, notice clustering in regions like Piedmont, Tuscany, and Sicily.

Left: An interactive map output from Scrapbook showing all wines we drank that came from France. Wines are clustered in regions like Bordeaux, Burgundy, and Provence. Right: An interactive map output from Scrapbook showing all wines we drank that came from Italy. Again, notice clustering in regions like Piedmont, Tuscany, and Sicily.

(

toc)

Conclusion

In this post, we’ve talked about some of our key inspirations for Scrapbook, namely the memex, MyLifeBits,

Wunderkammers, and the idea of a

vademecum along the lines of the primer in the science fiction story of

The Diamond Age. With those influences and others spurring us on, we’ve logged lots of coding hours to make Scrapbook a reality. But Scrapbook is more than software: it’s a way of life for us.

If you have read this far, obvious questions may linger. You might be wondering: is this for me? Is this for the average person? Do I have the skills to do this? Do I care? These are all valid questions. Here are some responses. Scrapbook in its current state – as software and a way of life – isn’t for everyone, not even most people. Most people won’t have the programming skills to run it – even the simpler

Scrapbook101 project. But what we’ve have found is that most people get what Scrapbook is and are generally interesting in the problem it is trying to solve. People we talk to would love something like Scrapbook. (We wanted something like it and that’s why we created it.) The challenge for us is to simplify and turn Scrapbook into something that can be more widely used.

One idea that we’ve touched on several times in this piece as well in several of the references we mentioned, is that most people generally won’t take the time to curate or annotate their data (or more generally any media they are trying to organize) to a sufficient degree to support rich queries. Just ask any person next to you how they manage their photos or documents. Chances are you’ll hear they don’t and sure wish they could, or if they do, it’s spread out and a mess.

Why don’t people curate their personal data more? The answer comes down to lack of time and energy. With so many other daily worries, few have the time and energy to do what we are doing, especially when the return on investment is not immediately obvious? For sure, curating data in a private repository – as we do with Scrapbook – is a passion for us. We understand it’s a hard sell to others less passionate about personal information management, others with less time and energy, and others less clear about the potential reward. And all this is especially true when doing so isn’t critical to living…yet. Might there be some future time when curating your data will be critical to living well or even surviving? Imagine a future, and not necessarily a dystopian one, where recalling small, seemingly banal details becomes important. Ask yourself how easily you could do that and where that data would live. Would your data be under your control and visible by who?

All said, it’s our desire to remember details of our life and tell our story in way that we have control over that drives us forward. A story with backing data that’s under our control and not commoditized. (Our cabinet of curiosities will not include ads!) Scrapbook can and will to be made simpler in time, but it will always fight an uphill battle with the slick features in the current crop of centralized online and social media services (

e.g., FAMGA) or future ones not yet developed. In such services, it’s now relatively easy to accumulate and share a digital representation of your life without much fuss or curation, you only need sign up and hand over your data. But for us, that is a price too high to pay.

We imagine a future where Scrapbook evolves to be as easy to use as Facebook or Snapchat, such that the cost of entry and data curation crosses the benefit threshold for the average person. And we imagine the capability of managing your own Scrapbook and telling your own story with you as the user in full control of your own data. We feel emboldened by the possibility of real-time capture-and-share to Scrapbook from any device with machine learning to help contextualize and develop stub Scrapbook entries that you can be prompted to expand on later. We are excited about capturing the rich data locked in static calendars and email and making the data dynamic. And, what if we could tap into timelines built or tracked in other services and use them in Scrapbook? All of these sources of data – we imagine – can be combined and modeled with relationships connecting data and rich story telling aspects that benefit you, the user.

(

toc)

References

All references were last accessed on February 2019.

E. Adar, D. Karger, L.A. Stein, “

Haystack: Per-User Information Environments”, 1999.

- Describes an Information Retrieval (IR) system designed for an individual and his corpus (information).

- “The Haystack project aims to make a digital IR system that is less like a library and more like a personal bookshelf.”

- Focused on managing communication, email, documents, references, bookmarks, etc.

- Has the interesting idea of three sources of data: data driven clients, observers, human annotation.

M. Alper, “

Learning in the ‘Diamond’ (or, the digital) ‘Age’ (Part 1)”, 2011.

- Makes the point that for all that the primer is technologically and as a solo activity that behind its social interactions and human communication matter. This is clearly demonstrated by how the three young girls turn out differently based on the varying amounts of interaction and communication each had with her primer.

Gordon Bell, Jim Gemmell, “Your Life, Uploaded: The Digital Way to Better Memory, Health, and Productivity”, 2002. (

Amazon)

DARPA “

LifeLog” project.

- Canceled in 2004, Wayback Machine archive.

D.C. Engelbart, “

Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework”, 1962.

Geoffrey A. Fowler, “

What happened when I told Marie Kondo I have a better, higher-tech method of tidying up”, 2019.

Robert W. Gehl, "

YouTube As Archive: Who Will Curate This Digital Wunderkammer?". International Journal of Cultural Studies. 12 (1): 43–60, 2009.

- “In archives, all content is flattened and has equal weight, so it is up to a curatorial authority to present content to audiences. While YouTube promises to democratize media, its lack of a centralized ‘curator’ sets the stage for large media corporations to step into the curatorial role and decide how each object in YouTube’s archives will be presented to users.”

J. Gemmell, A. Aris, R. Lueder, “

Telling Stories with MyLifeBits”, 2005.

J. Gemmell, G. Bell, R. Lueder, “

MyLifeBits: fulfilling the Memex vision”, 2002.

- A project dedicated to digital personal lifetime storage for all an individual’s digital media.

- Points out that passing on information for posterity is also something that should be considered.

Katie Day Good, "

From scrapbook to Facebook: A history of personal media assemblage and archives", 2012.

- Highlights similarities between print-era scrapbooks and contemporary social media.

Gordon Grice, “

Cabinet of Curiosities: Collecting and Understanding the Wonders of the Natural World”, 2015.

- How to start your own physical cabinet of curiosities.

Kashmir Hill, “

I Cut the ‘Big Five’ Tech Giants From My Life. It was Hell”, 2019.

Indie Web

- “Whatever the reason, you’re done with sharecropping your content, your identity, and your self.”

R. Jain, “Multimedia Electronic Chronicles”,

IEEE Multimedia, July 2003. (

abstract and purchase)

D. Karger, “Haystack: Per User Information Environments

”, 2006. (

abstract and purchase)

- A swiss army knife of a system that “stores (references to) arbitrary objects of interest to the user. It records arbitrary properties of the stored information, and relationships to other arbitrary objects. Its user interface flexes to present whatever properties and relationships are stored, in a meaningful fashion.”

D. Lavenda, “

The Memex: The Personal Memory Extender That Never Was”, May 2011.

- The author makes the interesting point that when comparing memex to Hypertext/web, memex is about two-way nature, relationships are created and consumed in memex while on web they are mostly consumed.

Laura Parker, “

How to Become Virtually Immortal”, The New Yorker, 2014.

L.C. Smith, “Memex as an Image of Potentiality in information Retrieval Research and Development”, SIGIR ’80: Proceedings of the 3

rd annual ACM conference on Research and Development in information retrieval, 1980. (

abstract and purchase)

R.H. Veith, “Memex at 60: Internet or iPod?”, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 57(9): 1233-1242, 2006. (

abstract and purchase)

J. Udell, “

Hosted lifebits”, 2007.

A. Watters, “

Memory Machines: Education Technology Without the Memex”, 2015.

- Interesting point that human memory is different than computer memory. “Human memory is different. The story – the memory – will change over time. It can be embellished; it can be forgotten. We forget by design.”

Wired, “

Pentagon Kills Lifelog Project”, 2004.