When I write, I tend to use a combination of lowercase block letters and cursive, as I believe many Americans do. What I find fascinating in Italy is the preference for stampatello maiuscolo or uppercase block letters when writing. I often ask people to write in my little black notebook and almost always they do so using uppercase block lettering. (Yeah, I'm that kind of person who shoves a notebook in front of you and asks you to write something down.)

Here are six examples from the last few months.

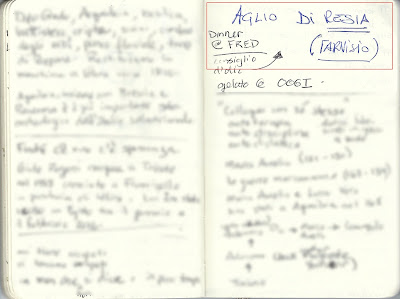

Sample 1

Who: Middle-aged man

Where: Udine

Context: We ate at an enoteca called Fred in Udine, and one of the staff wrote the name of a particular garlic we tasted called Aglio di Resia from Tarvisio.

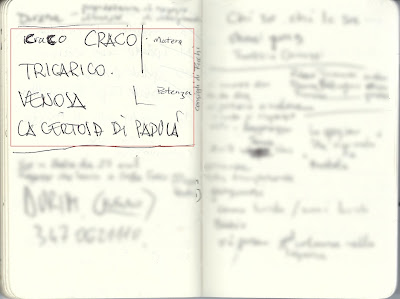

Sample 2

Who: Older woman

Where: Bergamo

Context: One morning, in our local café, Bar Papavero, I was talking with a friend whose family is from Basilicata and she was listing places to see there including: Craco, Tricarico, Venosa, and La Certosa di Padula.

Sample 3

Who: Middle-aged woman

Where: Outskirts of Bergamo

Context: After lunch one day at Trattoria all'Alpino (great walk from Bergamo, see here), we were talking to the owners and told them that we would be going to Friuli-Venezia Giulia in a few days. They wrote down a few suggestions that might be of interest to us. They were: Maniago – a city known for its production of steel blades, Vajont – location of the disaster that killed over 1,900 people in 1963, and the Sequals, the home town of the Italian boxer Primo Carnera.

Sample 4 (two samples)

Who: Middle-aged woman and a female teenager

Where: Bergamo

Context: In Bar Papavero, I first asked Eleonora for her telephone number, which she wrote down. Next, I asked the granddaughter of one of the café regulars to write down a saying we were talking about. That saying is: prendi l'arte e mettila da parte – basically meaning, learn what you can, because you'll never know when you'll need it.

Sample 5

Who: Middle-aged man

Where: Cuneo

Context: Talking with one of our "cousins" we got a suggestion on something to visit while staying in Piedmont. He wrote: Ormea / Alto / Caprauna / [undecipherable] / Cantarana / Upega / Ponte di Nava – all towns in the Cuneo Province of Piedmont, close to the French border.

Sample 6 (two samples)

Who: Two different middle-aged women

Where: Bergamo

Context: One sample is during a discussion at Café Bar Papavero when I was talking with a woman about the Italian writer, translator, and journalist Fernanda Pivano. The second sample is from a woman who was on a guided tour of Bergamo's iconic Roccolo di Castagneta (Tavernella).

A roccolo is basically a big bird trap. For more information on roccoli, see A Walk from Albino to Bergamo via Monte Misma. During the visit of the Roccolo di Castagneta, the guide described wooden instruments that were thrown to simulate a bird of prey so that smaller birds would be frightened and hopefully fly into a waiting net. The device is called a spauracchio in Italian. The woman I asked thoughtfully wrote it in Bergamasco dialect as well – sboradur – always in capital letters.

Many other samples

Who: Various

Where: Bergamo

Context: See the series on Street Sign Language Lessons, for example, Bergamo – Coronavirus – Street Sign Language Lesson XXXI. Many of the signs are in all caps, from friendly to not-so friendly signs.

This Italian expert in the study of handwriting and criminology discusses some ideas about why Italians use stampatello. The author suggests wide-ranging reasons including hiding one's tender side (cursive being more vulnerable?), avoiding being judged by other (bad writing?), looking for independence and asserting oneself (by adopting what everyone else does?), or just wanting to be legible (and sort of a conformist?).

These may be all valid reasons, but we add two other possible reasons. The first is that Italy, a country with many dialects and languages, still struggles to achieve unification in the sense that other European countries have and maybe stampatello is one small way of being unified. It was Massimo D'Azeglio who said of the unification of Italy in 1861: "Fatta l'Italia, bisogna fare gli italiani", meaning "Italy is done, the Italians need to be made". He was referring to the separate cultures, traditions, and languages (dialects) between the newly united regions.

The second reason for stampatello use is that the Italian alphabet derives from the Latin alphabet and the latter started out as roman square capitals. Many roman inscriptions with square capitals adorn buildings and monuments evoking authority. Could it be that Italian's use of capital letters derives from this history?

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments are moderated. If your comment doesn't appear right away, it was likely accepted. Check back in a day if you asked a question.