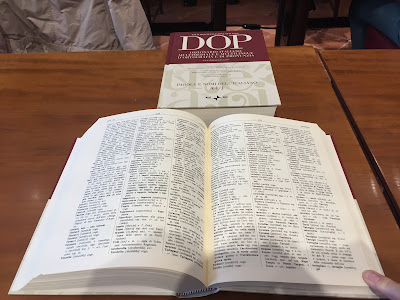

Italian dictionaries consulted for this post: DOP, Hoepli, de Mauro.

Italian dictionaries consulted for this post: DOP, Hoepli, de Mauro.

Overview

(

top)

I'm obsessed with tonic accents. I admit it. I think it stems from having so much trouble with pronouncing Italian words and, in particular, knowing what syllable to stress. I've discussed tonic accents in several other posts, including

Italian Words with Tonic Stress on Third-From-Last Syllable: Le Parole Sdrucciole and

Conjugating Italian Verbs and Knowing Where to Put the Tonic Stress. Basically, the bane of my existence are

sdrucciole words, that is, words with an accent on the third-from-last syllable.

In this post, I'll talk about pronouncing people and place names, which, in my opinion, are not well-documented, at least from the point of view of someone trying to learn the language. It may sound like I'm making a big deal out of this, but after getting laughed at recently for my pronunciation of Taranto and Cattaneo, I decided to investigate further and hopefully save readers the same embarrassment.

For the record, I pronounced Taranto (a city) as Tarànto instead of correctly as

Tàranto. Hear the difference? My pronunciation of Taranto - normally written without the accent - got a chuckle and a quick correction. Then, I pronounced Cattaneo (a surname) as Cattanèo instead of Cattàneo. For that mispronunciation I was laughed at a good bit and called a

terrone, or southerner. I was among friends who (I hope) didn't mean it, but I was still a little annoyed.

What I found interesting in my research for this post is that many of the typical references I use daily have no information on how to pronounce people and places names and I needed some new references. I hope that after reading this post you'll walk away with a list of useful Italian dictionary references, with a few that can help you resolve pronunciation.

First, this post lists people and places names with the correct syllable to stress. Then, there is a quick overview of accents and vowels. Finally, the post finishes with a comparison of different references used to find pronunciation information (or not as the case may be). From the analysis of references, I recommend that the best overall site for quickly looking up pronunciation of people and places to be

DOP: Dizionario Italiano multimediale e multilingue d'ortografia e di pronuncia. Second to that, Wikipedia entries for place names often show their dialect form of the word and with accent mark, which is helpful. An example is the town of

Cedegolo in Val Camonica in the province of Brescia, Lombardy. In the Camunia dialect, the town is called

Sedégol.

People and Places List

(

top)

Here is a list of just a few of the places names I've wonder about (either by reading or driving by them in a car) and eventually looked up during my Italian language odyssey. The

RAI: Dizionario italiano multimediale e multilingue d'Ortografia e di Pronunzia is the main reference source in terms of accents shown. Note that accents are almost always

not used when you see these names written. They are included here only for clarity. See the next section for more information on accents and vowels.

People

Achìlle, Amlèto, Anassimàndro, Anassàgora, Archimède, Aristòtele, Aristàrco, Bàbila, (Alessandro) Barìcco, (Giacomo) Bresàdola, (Michelangelo) Buonarròti, (Primo) Carnèra, (Giacomo) Casanòva, (Andrea) Camillèri, (Carlo) Cattàneo, (Gaio Guilio) Césare, (Marco Tullio) Ciceróne, Cleòmene, (Cristoforo) Cólombo, (Niccolò) Copèrnico, (Francesco) Cossìga, Demòcrito, Diògene, (Gaetano) Donizétti, (Luigi) Einàudi, Empèdocle, Epicùro, Eràclito, Èrcole, Eròdoto, Èttore, Euclìde, Eurìpide, (Ugo) Fóscolo, (Alcide) de Gàsperi, Artemìsia Gentiléschi, Golìa, Ìcaro, Ippòcrate, (Éttore) Majoràna, (Dacia) Maraìni, Mèdici, (Alberto) Moràvia, (Pietro) Paleòcapa, Parmènide, Pitàgora, Platóne, Polifèmo, Promèteo, Rómolo, San Bàbila, (Leonardo) Sciàscia, Sòcrate, (Antonio) Stoppàni, Tàntalo, Tolomèo, Tucìdide, Zenóne

Places

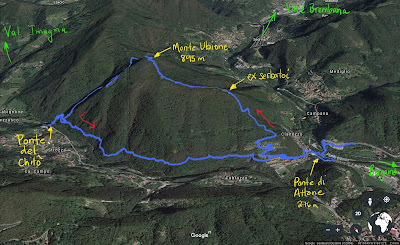

Abrùzzo, Adamèllo (monte), Àdige (Trentino-Alto Adige), Àgordo, Alberobèllo, Albisòla Marina (Savona, Liguria), Alghèro, Almè, Amatrìce, Ancóna, Àquila, Aràbba, Ardèsio, Arlùno, Àsolo, Atène, Balòcco, Bèrgamo, Brembàte, Bréscia, Brìndisi (Brindisi, Puglia), Càgliari, Campània, Cantagàllo (Prato, Toscana), Caracàlla, Cardìto (Napoli, Capania), Carisòlo (Trento, Trentino-Alto Adige), Casèrta, Catanzàro (Catanzaro, Calabria), Cecìna (Brescia, Lombardia), Cècina (Livorno, Toscano), Cedégolo (Brescia, Lombardy), Cèglie Messàpica (Brindisi, Puglia), Centàllo (Cuneo, Piemonte), Cervère, Cividàle del Friùli, Cìvita di Bagnoregio (Viterbo, Lazio), Cofano (Monte Còfano, Sicilia), Cormàno, Cremóna, Cùneo, Dàlmine, Èboli, Edimbùrgo, Éllero (fiume), Émpoli, Èrice, Firènze, Fòppolo, Fossàno, Friùli, Gallìpoli, Gènova, Grottàglie, Ìmola, Itàlia, Jèsolo (Venezia, Veneto), Legnàno, Linàte, Livórno, Lizzòla (Bergamo, Lombardia), Lombardìa, Lònguelo, Lóvere, Màntova (Mantova, Lombardia), Marcàllo, Massàfra (Taranto, Puglia), Matèra, Mésero, Milàno, Milàzzo, Mòdena, Molìse, Mònaco dei Bavièra, Monte Bastìa, Nago-Tórbole, Nàpoli, Nèbrodi (monti Nebrodi, Sicilia), Nèive, Òrio al Sèrio, Ostùni, Òtranto, Pàdova, Padùla, Paèstum, Pantellerìa (Trapani, Sicilia), Pavìa (Lombardia), Pegognaga (Mantova, Lombardia), Perùgia (Umbria), Pésaro, Pescàra, Piacènza, Piemónte, Pitigliano (Grosseto, Toscana), Pizzo Fòrmico, Policòro, Ponte Càffaro (Brescia, Lombardia), Prèmolo, Radicòfani (Siena, Toscana), Ragùsa, Róma, Rovìgo (Veneto), San Càndido (Bolzano, Trentino-Alto Adige), Sant'Angelo in Lìzzola (Pesaro e Urbino, Marche), Sardégna, Sàssari, Segràte, Selinùnte, Sèllero (Brescia, Lombardy), Senìse (Potenza, Basilicata), Seriàte, Sèrio, Sicìlia, Siracùsa, Sirmióne, Sorìsole, Spoléto, Stupinìgi, Tànaro (fiume), Tàranto, Tèramo, Tèrmoli (Campobasso, Molise), Tévere, Tìndari, Nago-Tórbole (Trento, Trintino-Alto Adige), Torìno, Tortóna, Tràcino (località su Pantelleria), Tramùtola(Potenza, Basilicata), Tràpani, Trevìso, Tronzàno, Turchìa, Ùdine, Val Vèrtova (Bergamo, Lombardia), Vèneto, Venèzia, Viaréggio (Lucca, Toscana), Vignàte, Vitèrbo, Voghèra, Zurìgo

Notes

Note 1. You might have noticed that many of the people listed are scientists or ancient Greeks. This is a function of what catches my eye. Sorry, you won't find movie star or soccer player names here.

Note 2. Also not included in the lists above are people or places that are normally written

with an accent. With these words, there is no ambiguity because the accent shows where to put the emphasis, namely at the end of the word. In Italian, the accent mark must be used when the tonic accent is on the last syllable.

Examples of people with accents marks in their names are:

Fabrizio De André, Antonio Curò, Mosè, Gesù

Examples of town names with accent marks are:

Almè (Bergamo, Lombardia), Bianzè (Vercelli, Piemonte), Barzanò (Lecco, Lombardia), Cagnò (Trento, Trentino-Alto Adige), Calavà (Messina, Sicilia), Canicattì (Agrigento, Sicilia), Carrù (Cuneo, Piemonte), Cirò (Crotone, Calabria), Colà (fraz. di Lazise, Verona, Veneto), Forlì (Forlì-Cesena, Emilia-Romagna), Gambolò (Pavia, Lombardia), Gariè (fraz. di Pianfei, Cuneo, Piemonte), Javré (Trento, Trentino-Alto Adige), Mondovì (Cuneo, Piemonte), Montà (Cuneo, Piemonte), Nardò (Lecce, Puglia), Ortisé (Trento, Trentino-Alto Adige), Pagò (fraz. di Venasca, Cuneo, Piemonte), Palanfrè (Vernante, Cuneo, Piemonte), Ruffré-Mendola (Trento, Trentino-Alto Adige), Salò (Brescia, Lombardia), Sanda-Vadò (fraz. di Moncalieri, Torino, Piemonte), Sandrà (fraz. di Castelnuovo del Garda, Verona, Veneto), Santhià (Vercelli, Piemonte), Sciàcca (Agrigento, Sicilia), Temù (Brescia, Lombardia), Verrès (Valle d'Aosta), Viganò (Lecco, Lombardia) Vò (La Valle del Vò, Bergamo, Lombardia)

Note 3. In terms of city names in Italy, the list above is a bit skewed to names in Lombardy and Piedmont because that's where we spend most of our time. You'll notice that there are a few names in the list ending in -ate such as Linate, Liscate, Segrate, Seriate, and Vignate, which is common in Lombardy. For more information, see

Toponimi di Bergamo e del Bergamasco and

Origine dei toponimi italiani. The suffix refers typically to a location near water, some other natural feature, or denotes a group of people related either by marriage or some other bond.

Note 4. On the subject of names, one first name that always trips me up is Niccolò and Nicola. Niccolò is written with the accent mark. Nicola is pronounced with tonic stress on O as Nicòla.

Note 5. In the place names you will notice that some words have different tonic accents depending on the region. For example, Lizzòla (Bergamo, Lombardia) stresses the second-to-the-last syllable while Sant'Angelo in Lìzzola (Pesaro e Urbino, Marche) stresses the third-to-the-last syllable. Cecina is another place name where the accent seems to change.

Vowels and Accent Marks

(

top)

This is slight digression, but may be of interest if you are wondering why E and O in the people and place names can have two different accents marks, while A, I, and U have just one mark.

- There are five written vowels (graphemes) in Italian: A, E, I, O, U. In English, we have the same five and sometimes Y.

- There are seven pronounced vowels (phonemes) in Italian, because E and O can be open or closed. The seven sounds are represented as /a/, /ɛ/, /e/, /i/, /ɔ/, /o/, and /u/. /ɛ/ and /e/ are E open and closed, respectively. /ɔ/ and /o/ are O open and closed, respectively.

- Each vocal sound has a location in the mouth where it originates as demonstrated in this vocal diagram for Italian. The vocal diagram for Italian is a triangle, while that for English is shaped like trapezoid.

- The five written vowels have the task of representing the seven pronounced vowels. Most of the time there isn't a problem. When there is, graphic symbols are used to clarify. This is particularly important when distinguishing between two words spelled the same (homographs) but with different pronunciations. A good example is the classic confusion between fruit and fish. Pèsca is fruit and pésca is fishing, where è represents the open sound /ɛ/ and é represents the closed sound /e/. Similarly, you might encounter vòlto, the past participle of volgere, and vólto, face, where ò represents the open sound /ɔ/ and ó represents the closed sound /o/.

Okay, after that quick intro to vowels, you need to keep in mind how accents on vowels are used in designating the accented syllable in a word.

- In the lists above of people and place names, it worth restating again that accent marks would not normally be used to show where the stress goes. They were added to make the discussion easier.

- When an A, I, or U are in the stressed syllable of a word, they appear as à, ì, and ù and they are pronounced as they usually are. It doesn't mean they are "closed" like E or O can be. Rather, it means the accent mark is just shows stress of the syllable.

- When and E or O are in the stressed syllable of a word, they can appear as è, é, ò, or ó. In this case, the accent mark shows both the stressed syllable and how the vowel is pronounced, i.e., as open or closed according the mark specified.

- When E or O are not part of the stressed syllable of a word, they are closed, i.e., /e/ and /o/. So the open sound is only possible when E and O are in the stressed syllable.

If you are a little confused and even stressed out (pun intended) by open and closed vocals, my advice is not to worry about them too much. In my experience, most Italians don't grasp this concept. In fact, one of my favorite language references

Grammatica italiana di base, says as much noting that much of the rules of the open and closed E and O originate for the most part from Tuscany. Outside of that region the spoken language diverges quite a bit. What I find more important than open and closed vowel sounds is getting the tonic accent correct.

Italian dictionaries consulted for this post: il Ragazzini, lo Zingarelli, Treccani.

Italian dictionaries consulted for this post: il Ragazzini, lo Zingarelli, Treccani.

Comparison of References

(

top)

To test how different dictionary sources might be used to help figure out pronunciation of people and place names, let's use two test words: Taranto, a city in Puglia, and Democrito (Democritus in English), a Greek philosopher. Both words have accent on the third from last syllable, Tàranto and Demòcrito, and were words I looked up to confirm pronunciation. The results of my research reveal that:

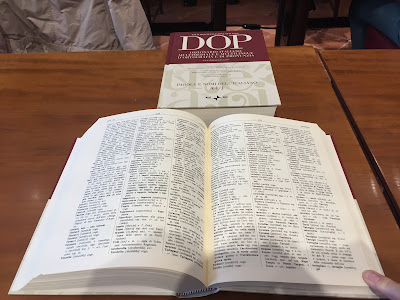

- The RAI DOP reference is the winner by far in terms of being a good source to resolve pronunciation; it's good online and offline (paper copy) for resolving people and place names.

- An encyclopedia app or web site such as Treccani or Wikipedia, are always a handy backup for resolving people and place names.

- Pronunciation sites like Forvo are helpful as well.

- Wikipedia entries can sometimes include the correct pronunciation, e.g., for Pesaro.

Key for tables below

listed - Word is listed with pronunciation and accent shown.

listed* - Word is listed but with no indicated pronunciation; there is a sound clip.

not listed - Word doesn't appear at all in the reference.

not listed* - Word doesn't appear, but a derivative or related word is present that could be useful.

Online resources

References I consult most frequently.

Physical books

These are references I found in Biblioteca Civica Angelo Mai, in Bergamo. I had expected paper sources would give better coverage of people and place names, but that wasn't the case.

| Word | RAIDOP1 | Hoepli2 | LoZing3 | Treccani

Vocab4 | TreccaniEnc5 | de Mauro6 | Il Ragazzini7 |

| Tàranto | listed | not listed | not listed | not listed | not listed | not listed | listed |

| Demòcrito | listed | not listed | not listed | not listed | listed | not listed |

not listed

|

1 RAI DOP: Dizionario Italiano multimediale e multilingue d'ortografia e di pronuncia. Parole e nomi dell'italiano.

2 Grande Dizionario Hoepli di Aldo Gabrielli, edizione speciale 150

o anniversario

3 Lo Zingarelli 2008, vocabolario della lingua italiana di Nicola Zingarelli, Zanichelli

4 Il Vocabolario della lingua italiana, Treccani

5 Vocabolario della lingua italiana, Treccani l'enciclopedia

6 Tulio de Maruo grande dizionario Italiano dell'uso

7 il Ragazzini, dizionario inglese italiano, italiano inglese di Giuseppe Ragazzini, Zanichelli

Apps

Here are four apps that I use frequently on my phone.

Related web pages