Left: Floor Plan of the Computer History Museum; Right: Difference Engine #2

The Computer History Museum started life in 1979 as the Digital Computer Museum inside of Digital Equipment Corporation’s office in Massachusetts. Today, it is an independent non-profit, located in Mountain View, California. The museum has a large and interesting collection worthy of a few hours of time if you are in the area and you are even mildly interested in computers. Compared to the nearby Intel Museum, I would recommend the Computer History Museum as your first stop, if not only to see the fascinating Babbage Difference Engine #2 in action. Call or write to ask when live demonstrations of the Different Engine #2 occur.

Left: Napier’s Bones, England, ca. 1700; Right: Hollerith Tabulating Machine

Some characters that caught my attention as I made my way through the main exhibition Revolution: The First 2000 Years of Computing.

- John Napier (1550 – 1617) invented (along with Henry Briggs) of logarithms. He also invented Napier’s Bones, rods for calculating products and quotients of numbers. The rods or “bones” are based on the concept of lattice multiplication, a way to break down multiplication into smaller steps. I can imagine nerds and geeks of the time having Napier’s Bones in their metaphorical shirt pockets…I would.

- Herman Hollerith (1860 – 1929) invented the Hollerith tabulating machine, first used in the 1890 U.S. census. His tabulator, based on punched cards, produced results twice as fast as other methods used in that census. The holes in a punch card encoded information about one person. Each card was fed into a tabulator that advanced clock-like dials based on where the holes were on the card. Hollerith’s company Tabulating Machine Company, merged with four other companies in 1911 to become one company that eventually was named International Business Machine Corporation (IBM) in 1924. Here is the museum’s description of the census effort: Making Sense of the Census: Hollerith’s Punched Card Solution.

- Seymour Cray (1925 – 1996), the “father of supercomputing” is featured prominently in the exhibition. Yes, the Cray-1 the museum has on display and the other one you can touch and walk into are really cool. (The Cray-1 was referred to some as the “world’s most expensive loveseat” due to its innovative design. The loveseat hid the power supply.) However, it was the video of Cray’s life and the detail about his “supposed” favorite pastime, digging tunnels under his house that really caught my attention. The video uses images from a 1932 Modern Mechanix and Inventions magazine article titled Tunnel Digging as a Hobby which was about one Dr. H. G. Dyar referred to as “the mole man of Washington” in a Washington Post article. I’m not sure how tunnels and computer history are related, but it stuck out in my mind. Here’s the video. The tunnel part is at 2:58.

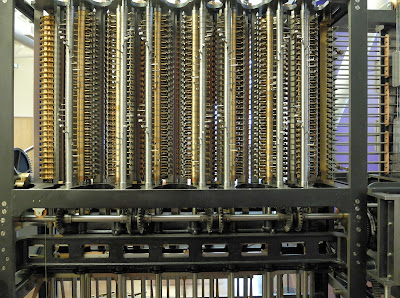

- Charles Babbage (1791 – 1871), the inventor of the incredible Difference Engine #2, a Victorian-era, hand-cranked, computing machine. All 8,000 parts of the engine work together to calculate values of a 7th order polynomial. Here’s a video on the museum’s site that shows the engine in action.

Babbage designed the machine in the late 1840s, but never built it. The fully functioning machine in the Computer History Museum is the second of two built based on Babbage’s original plans. The first was completed in 1991 and the second in 2008.

By all accounts (e.g., see The Philosophical Breakfast Club: Four Remarkable Friends Who Transformed Science and Changed the World by Laura J. Synder), Babbage was an prickly genius. He spanned the transformation of science (in the 19th century) when it moved from the hands of the gentlemen scientist / natural philosopher to the professional scientist we know it today.

I’ll mention two themes that recently I’ve been thinking and reading about in the history of computing. The first theme is the idea of simplifying a problem to a form that can be more easily solved. The second theme is how the role of humans has changed in time in the history of computing.

Napier’s Bones exhibit the simplification theme in that they reduce complex multiplication to simpler steps that can be easily understood. The Difference Engine #2 demonstrates the simplification theme a little more abstractly. The engine uses the concept of finite differences to turn the problem of finding values of a polynomial into a one of constructing simple tables based only on addition and subtraction. The prosthaphaeresis algorithm is another, classic example of simplification where multiplication and division are approximated using formulas from trigonometry and look-up tables.

Left: The Philosophical Breakfast Club. Cover shows portraits of Charles Babbage, John Herschel, William Whewell, and Richard Jones.

Right: When Computers Were Human. Cover shows an operator of a Pantograph Card Punch for creating cards that could be read in the Hollerith Tabulating Machine

The second theme of the changing role of humans in the history of computing is covered in the interesting book When Computers Were Human by David Alan Grier. The book “attempts to invert the history of scientific computing by narrating the stories of those who actually did the calculations.” True to the title, many of the stories are of people who were really “human computers”. For example, in the case of the Hollerith tabulating machine, humans collected the information, punched the cards, and then fed the cards to the tabulator. Humans were an integral if not manual part of the computing process.

For the Difference Engine #2, Babbage was inspired to “calculate with steam” as a way to reduce the number of errors in the mathematical tables so critically used in different fields of science. In Babbage’s time, those tables were constructed by “human computers”. The humans crunch numbers that were collected and rolled up into what might be a table of logarithms.

A humorous example of human computers, mentioned in When Computers Were Human and also detailed in the article "Work for the Hairdressers: The Production of de Prony's Logarithmic and Trigonometric Tables" by I. Grattan-Guiness, is how a large set of logarithmic and trigonometric tables were produced at the end of the 18th century under the direction of the French mathematician and engineer, Gaspard Riche de Prony (1755 – 1839). The production of the tables was based on three groups or sections working together. The first group chose the mathematical formulas. The second group set up the calculations based on the formulas and sent them to the third group which performed the bulk of the calculations (simple addition and subtraction):

These calculations were done by the third section [group], a large team of between 60 and 80 assistants. Many of these workers were unemployed hairdressers: one of the most hated symbols of the ancien regime was the hairstyles of the aristocracy, and the obligatory reduction of coiffure “as the geometers say, to its most simplest expression” left the hairdressing trade in a severe state of recession. Thus these artists were converted into elementary arithmeticians, executing only additions and subtractions.”

Another example of human computers that caught my attention is described by Grier in Chapter Two, The Children of Adam Smith. In 1765, the Royal Astronomer Nevil Maskelyne (1732 – 1811) was tasked with producing an almanac. The striking fact about the undertaking (at least to me) is that Maskelyne organized a cottage industry of human computers that received and sent their work through the mail. Grier describes it as follows:

For the Nautical Almanac computers, Maskelyne provided paper, ink, and instructions that were called “computing plans.” Maskelyne wrote these plans on one side of a heavy sheet of folded stationery. The instructions, scrawled in a slightly disheveled hand, summarized each step of the calculation. Occasionally, he would illustrate the computations with a hasty sketch of an astronomical triangle. On the other side of the paper he drew a blank table, ready for the computer to complete. [Grier, David Alan (2013-11-01). When Computers Were Human (p. 30). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.]

Maybe all this is a bit of nostalgia on my part. Today’s computing scene is too complex to grasp – at least at time – and it’s easier to take comfort in the past. Maybe I could be one of those human computers working on a logarithm table? Accordingly, it didn’t escape my notice that the bulk of my time at the Computer History Museum was spent with the pre-19th century devices.

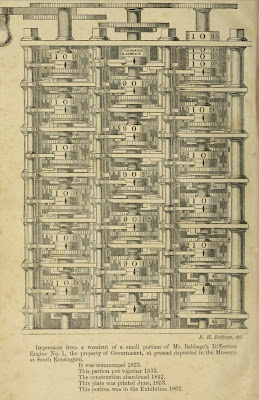

Left: Images of a small portion of Difference Image #1 from Passages from the Life of a Philosopher (1864) by Charles Babbage.

Right: Difference Engine #2 in the Computer History Museum, Mountain View, California

Left: IBM Watson versus Travelmarx (losing) on a Jeopardy! Stage Set at the Computer History Museum, Mountain View, California.

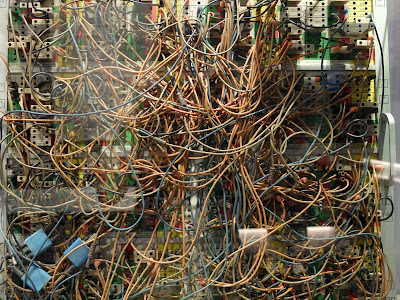

Right: EAI 580 Patch Panel - Electronic Associates, Inc. US, ca. 1968.

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments are moderated. If your comment doesn't appear right away, it was likely accepted. Check back in a day if you asked a question.