Left to Right: Arthur Schopenhauer, Charles Babbage, Luca Martini

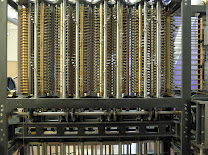

Recently, I've been thinking a lot about Charles Babbage. First, in the context of reading the book The Philosophical Breakfast Club: Four Remarkable Friends Who Transformed Science and Changed the World by Laura J. Synder. The four men are Charles Babbage, John Herschel, William Whewell, and Richard Jones. Synder discusses their lives and contributions during the time when science changed from hobby to profession. I encountered Babbage again at the Computer History Museum where I saw the Babbage Difference Engine #2 in action. What kind of person conceived this big mechanical calculator?

Obviously, Babbage was a visionary genus who was able to see the need for automated calculations and designed machines that could do them. Among other qualities often used describe Babbage are irascible, cranky, prone to bitterness (mostly later in his life), and apt to not forgive or forget perceived insults. It is this darker side that caught my attention in the last chapter of Synder’s book. In particular, Synder mentions a chapter from Babbage's Passages from the Life of a Philosopher [1864], which was based on a pamphlet he published called Street Nuisances. As Synder describes it:

Babbage’s difficulties in concentrating led him to believe that his work was being sabotaged by street musicians, especially “organ grinders,” men who went from house to house making music and hoping for some coins in return. These men— many of them immigrants from Italy— would travel through neighborhoods holding large barrel organs.

Babbage lashed out, yelling at the offenders from his window, prosecuting the organ grinders in the courts, and finally publishing a pamphlet on “Street Nuisances,” which he reprinted in his Passages from the Life of a Philosopher. Retaliatory mobs began to follow him about, sometimes one hundred people at a time, shouting and banging on tin drums and blowing horns; dead cats were left on his doorstep, windows were broken, threats on his life were made. 82 Children from the local schools would shout out his name “coupled with offensive adjuncts” whenever they passed the windows of his house.

[Snyder, Laura J. (2011-02-22). The Philosophical Breakfast Club: Four Remarkable Friends Who Transformed Science and Changed the World (pp. 356-357). Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.]

Ironically, organ grinders turn a crank to produce a result (noise for Babbage) and the difference engine works by turning a crank to produce a result (a calculation, music to Babbage’s ears likely).

Left to Right: Babbage Difference Engine #2, Organ Grinder, Babbage’s List of Street Nuisances

In the chapter Street Nuisances, in Passages, Babbage comes across as inflexible and crotchety, filled with rancor. His solution to only use public roads for traveling and not for business or amusement doesn’t seem practical even if it might reduce his dreaded street nuisances. And, his disdain for anybody who enjoys music is a perhaps a bit too general: “Those whose thoughts are chiefly occupied with frivolous pursuits or with any other pursuits requiring but little attention from the reasoning or the reflective powers, readily attend to occasional street music.”

These nits aside, I could not help but feel empathy for Babbage and his war against street nuisances. You can sense the frustration and anger in his tone when he writes about noise. He calls the chapter Street Nuisances, but, he could just as well have called it On Noise; he probably would not have included a chapter about street pantomimes.

Cue Schopenhauer

The Babbage chapter reminds me of the essay from Arthur Schopenhauer, On noise, discussed in a previous post, Schopenhauer, On Noise. At the time we wrote that entry, we were living in Florence, and a certain lady and her brood slammed a certain green door with seemingly gleeful abandon that drove me crazy. (We lived above the door. Couldn’t they just quietly close it?) Schopenhauer said in the essay:

There are people, it is true—nay, a great many people—who smile at such things, because they are not sensitive to noise; but they are just the very people who are also not sensitive to argument, or thought, or poetry, or art, in a word, to any kind of intellectual influence. The reason of it is that the tissue of their brains is of a very rough and coarse quality. On the other hand, noise is a torture to intellectual people.

Why are some people more sensitive to noise and others not? I'm writing this as I sit in an apartment (a rented room on a business trip) where the noise from the floor above is merciless. Does anybody else hear it? Am I going crazy?

L’angolo italiano

Babbage singles out Italian organ grinders in Street Nuisances. They are the start of a list of musical performers he finds annoying. Schopenhauer mentions a poem by the Italian painter and poet Bronzino (see child sprezzatura) which describes how noisy a small Italian town can be. The poem Schopenhauer refers to is: Il terzo libro delle opere burlesche aggiunto a quelle di m.Francesco Berni, page 288. The title is De’ Romori, A Messer Luca Martini and it starts:

Poichè, l’infermità vostra, e la mia

N’impedisce il vederli, e’l ragionare,

La penna invece d’occhi, e lingua sia

Ogni mattina il nostro singulare

Maestro mi dà nuove, o Luca mio,

Come la fate, e la siete per fare.

Luca Martini was a Renaissance engineer and friend of Bronzino. My Renaissance Italian translation capabilities are a bit rusty, but the verse doesn’t seem to have quite the same anger that Schopenhauer or Babbage project, but noise or “romor/romori” (in modern Italian it’s rumore) is mentioned many times. The noise of children (romor de’ fanciulli), bells (de le campane, e da i romor discosto), pots and pans that wreck the sleep (sento di piatti, tegami, e scodelle che m'ha per tutta notte il sonno gausto) and even normally “graceful” cats making noise at night (Anche le gatte o che leggiadra usanza trovò natura, arrabbiando la notte, Fanno tanto rumori). What’s not clear is whether the noises bothered Bronzino, Martini, both, or neither and if this was just a mediation on a noisy town. And, Bronzino didn’t mention the green door (la porta verde). Now that would have been cool (fantastico)!

Addendum 2025

A reader asked a question that prompted some further research, from which we learned:

- It's likely that Schopenhauer incorrectly attributed the De' Romori: a Messer Luca Martini chapter to Bronzino whereas it was written by Francesco Berni (1497/98 - 1535).

- De' Romori appears in a larger work of opera burlesche by Berni. It seems that work was reprinted and added to in subsequent years so that it's confusing to tell what you are looking at at times.

- We can say the De' Romori chapter is addressed to Luca Martini and chronicles the noise of the city. What we don't know is if Berni was serious or satirical; likely the latter. And, why would he write to Martini other than they were friends?

- The De' Romori chapter is only a few pages long and is written in an Italian that I have a hard time translating given my so-so Italian skills.

- The chapter talks about the various sources of noise and disturbances around the speaker's living quarters, including a kitchen, a shop, and other activities that cause noise. It paints a vivid picture of the cacophony of daily life.

- The introductory piece above doesn't really have an noise related bits; you have to get into the chapter a little ways.

.JPG)